Contemporary Adventures with The Garden of Earthly Delights: Open Worlds and Hieronymus Bosch

Abstract Over 500 years after it was created, Hieronymus Bosch’s The Garden of Earthly Delights continues to intrigue viewers. It has inspired contemporary artwork across diverse media including experimental film, digital animation and video games, as well as providing stimuli for curators, critics and collectors. This article maps present-day approaches to The Garden of Earthly Delights and links the enduring appeal of this painting to its interactive, multi-layered structure in which countless narrative vignettes play out simultaneously. Contemporary artworks that reference Bosch’s triptych are examined, with a special focus on digital creations by SMACK, Miao Xiaochun, Michael Bielicky and Kamila B. Richter. The exhibition The Garden of Earthly Delights Through the Artworks of Colección SOLO is also analyzed to illustrate how an understanding of Bosch’s work as interactive art informed the exhibition discourse, publication and architecture.

Keywords Hieronymus Bosch. The Garden of Earthly Delights. Contemporary art. New media art. Digital art. Open worlds. Megadungeon. Exhibition design.

1 Introduction

The triptych by Hieronymus Bosch (Jheronimus van Aken) known as The Garden of Earthly Delights is one of the world’s most recognisable paintings. Housed at the Prado Museum, Madrid, it is viewed each year by millions of visitors, while its fantastical scenes have brought the term ‘Boschian’ into the popular lexicon as a synonym for all things bizarre or weirdly hellish. The work is easily accessible online, while its imagery can be found on a dizzying array of products, from bikinis to Dr. Marten boots.1

1 An interactive, high resolution reproduction is available at https://archief.ntr.nl/tuinderlusten/en.html#.

While present-day references to The Garden of Earthly Delights are widespread, written historical sources on this iconic painting are very limited. The original title is unknown and documentation to conclusively establish a production date or patron is lacking. Most records on the painter’s life have also been lost, leaving fertile ground for scholarly debate on his ideas, motivations and sources of inspiration. Colourful and conflicting theories, together with the work’s rich, highly imaginative content, have turned The Garden of Earthly Delights into an experimentation site for numerous contemporary artists and curators.

This paper suggests that the megadungeon concept can shed light on these contemporary approaches to The Garden of Earthly Delights. Bosch’s triptych itself, it will be argued, can be viewed as a multi-layered experience, an open world in which various different pathways may be explored. Three of these routes – fantasy, sex and space – are used to map and contextualize a selection of contemporary artworks inspired by Bosch’s painting.

The digital artworks Microcosm (2008) by Miao Xiaochun, The Garden of Error and Decay (2010) by Michael Bielicky and Kamila B. Richter, and Speculum (2016‑19) by SMACK, are then examined in detail. Like The Garden of Earthly Delights, these are immersive spaces, ripe with symbolism, conceived to invite conversation. Finally, The Garden of Earthly Delights through the Artworks of Colección SOLO (Matadero Madrid, 7 October 2021‑27 February 2022) is also analyzed to illustrate how an understanding of Bosch’s work as interactive art informed the discourse, publication and architecture of a major exhibition.

2 A Labyrinth to Explore

The year after Hieronymus Bosch’s death, Antonio de Beatis, secretary to the Italian cardinal Luigi d’Aragona, visited Count Henry III of Nassau at Coudenberg Palace, Brussels. His journal entry for 30 July 1517 includes what Gombrich identified as the earliest surviving description of The Garden of Earthly Delights:

Ce son poi alcune tavole de diverse bizzerrie, dove se contrafanno mari, aeri, boschi, campagne et molte altre cose, tali che escono da una cozza marina, altri che cacano grue, donne et homini et bianchi et negri de diversi acti et modi, ucelli, animali de ogni sorte et con molta naturalità, cosi tanto piacevole et fantastiche che ad quelli che non ne hanno cognitione in nullo modo se li potriano ben descrivere. (Gombrich 1967, 403)2

2 En. transl: “There are some paintings of diverse bizarre things, representing seas, skies, woods, fields and many other things, such as some who emerge from a sea mussel, others who are defecated by cranes, women and men both white and black in diverse actions and poses, birds, animals of all sorts and with much naturalness, things so pleasant and fantastic that to those who have no knowledge of it, it cannot be described well in any way” (transl. by R. Falkenburg 2016).

In the 500 years since, Bosch’s artwork has given rise to innumerable descriptions, theories and studies. By the mid-sixteenth century, the artist was described as a “devil maker” (Koldeweij 2001, 100) – an epithet reflected in the title of the first monograph (Gossart 1907) – and has since been cast as a member of different heretical sects (Fraenger 1947; Harris 1995), an alchemist and consumer of rye-bread mould proto-LSD (Dixon 2003).3

3 A literature review is provided in Marijnissen ([1987] 2007, 84‑102). To coincide with the 500th anniversary of the artist’s death, exhibition catalogues were also published by the Prado Museum (Maroto 2016a) and Het Noordbrabants Museum (Ilsink, Koldeweij 2016), both of which include comprehensive bibliographical information.

Although the most extravagant speculations are generally rejected by Bosch scholarship, the quantity and variety of approaches is significant in itself. Bosch’s imagery – in particular The Garden of Earthly Delights, in which diverse visual narratives take place simultaneously – provides an enabling space for the imagination, presenting the viewer with a series of open worlds begging to be explored.

The Garden of Earthly Delights is now thought to have been painted c. 1490‑1500, most likely commissioned by Engelbert II of Nassau or his nephew, Henry III. The original title of the work is unknown, current usage dating from the nineteenth century. On arrival to El Escorial Monastery in 1593, it was registered simply as: “una pintura de la variedad del mundo, que llaman el Madroño” (Maroto 2016a, 330, ‘a painting on the variety of the world, which they call the Strawberry Tree’).

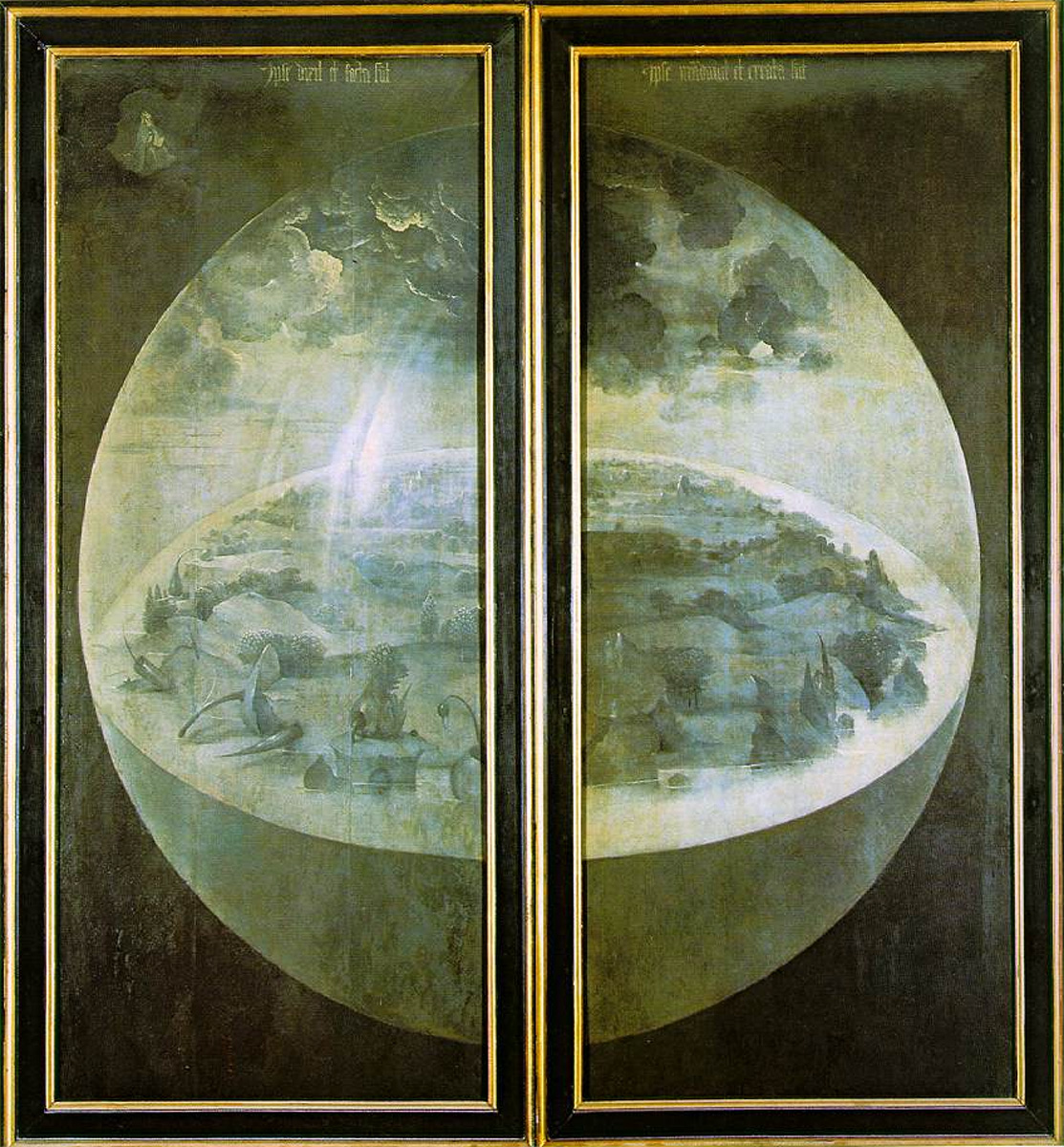

When closed, the triptych’s outer panels show the world on the third day of creation [fig. 1]. Within a giant, glass-like orb, bulbous plants emerge from a watery landscape while God looks on from above. Once opened, grisaille gives way to spectacular colour and a wealth of interconnected scenes [fig. 2]. In the left panel, Paradise, God the Father presents Eve to Adam in a fanciful landscape dominated by shades of green, pink and blue, in which hybrid creatures coexist alongside exotic animals including a giraffe and an elephant. This scene is connected by a single horizon line to the central panel, The Garden of Earthly Delights, in which couples or groups of naked figures engage in playful and sexual activities. Bizarre architectural constructions punctuate the landscape, while oversized birds and fruits add to its dreamlike or otherworldly feel. Hell, depicted in the right panel, shows all manner of punishments, including characters tortured on giant musical instruments or devoured and excreted by a beaked hybrid. In the centre, the enigmatic Tree Man gazes back from a scene of suffering and destruction which stretches from the frozen waters beneath him to the burning buildings in the distant background.

Although Bosch’s imagery can appear outlandish to the modern gaze, The Garden of Earthly Delights is packed with visual references which would have made its storyline clear to its intended audience. To late-Medieval viewers, the fish was a phallic symbol, rabbits and birds referenced sexual activity and musical instruments could point to decadence or sloth. As Gibson explains, strawberry bushes were viewed as a hiding place for the devil and symbolized the fleeting nature of pleasure (Gibson 2003). What emerges, then, is a fairly straightforward narrative: keep your libido in check or the afterlife is bleak.

The Garden of Earthly Delights, however, is far more than a simple warning on the dangers of lust. In Hell, a whole range of sins are punished, including avarice and gluttony, while gambling, music and the nature of chivalry are all called into question. As Reindert Falkenburg has convincingly argued (2011; 2016), this triptych can be viewed within the ‘princely mirror’ genre, a starting point for discussion or reflection – speculatio – on the state of the world and one’s place within it. This perspective is of particular relevance with regard to contemporary iterations of The Garden of Earthly Delights, especially the digital works discussed in Section 4.

Connected to its likely role as a conversation starter is another aspect of The Garden of Earthly Delights, essential to bear in mind when examining contemporary approaches: the triptych as an experience. The art critic Waldemar Januszczak observes: “When you walk into it you feel as if you’re walking into a landscape. It has a physical scale that impacts on you” (Ramirez 2017).

Figure 1 Hieronymus Bosch, The Third Day of Creation. Outer panels of The Garden of Earthly Delights Triptych. Ca. 1490‑1500. Oil on oak panels. 220 × 195 cm. Madrid, Prado Museum

This effect was clearly not lost on early viewers. In secular settings, triptychs were generally displayed closed, to be opened only on special occasions for high-ranking visitors. The experience of Bosch’s work would be journey-like, starting from the grisaille exterior, through the triptych’s doors, into a world of unbridled fantasy. As Gombrich noted (1967, 405), the tone of Antonio de Beatis’s account, far from focussing on the religious or moralizing features of the painting, seems to suggest entertainment or amusement. Court visitors were used to enjoying entremets – performances or tableaux vivants staged as breaks during elaborate banquets – and Falkenburg links these to playful scenes in The Garden of Earthly Delights (2016, 148). It is perhaps not too fanciful to suggest that the work itself provided a form of home entertainment for Henry III of Nassau and his guests.

Figure 2 Hieronymus Bosch, The Garden of Earthly Delights Triptych. Ca. 1490‑1500. Oil on oak panels. 185.8 × 172.5 cm (centre panel); 185.8 × 76.5 cm (left and right panels). Madrid, Prado Museum

This viewpoint resonates in a contemporary art landscape where immersive experiences, virtual or mixed-reality environments and the metaverse are all the order of the day. Notions of stepping inside or repopulating The Garden of Earthly Delights are common to a number of present-day approaches, while the original’s wealth of narrative scenes appeals directly to contemporary tastes, shaped by gamification, digital experience and interconnectedness. The Third Day of Creation, on the triptych’s closed shutters, will seem strikingly familiar to users of geographic information systems or fans of drone imagery. Bosch presents the viewer simultaneously with an entire planet and close-ups of individual rocks or plants, as though we have zoomed in on the watery orb. As Asa Mittman observes:

The vantage afforded by Bosch to the supreme deity is the very viewpoint presented by Google Earth as we hover, held aloft by an unseen force, as far above or as close to the surface of the planet as we wish. (Mittman 2012, 940)

Modern-day viewers familiar with the labyrinthine structures of fantasy role playing, open world or sandbox games will have no difficulty in recognizing the ‘portals’ employed by Bosch. The left panel, Paradise, features a number of images used to indicate that sin is already present: an owl – a symbol for evil or the Devil – gazes out from a circular opening in the central structure, while in the foreground, sinister creatures emerge from a dark pool whose colour palette seems to connect directly with Hell. Layered, intersecting scenes dominate in Paradise and Hell, which both feature numerous examples of worlds within worlds, from bell shaped corollas inhabited by couples or trios to the iconic Tree Man, whose body doubles up as a tavern.

Of course, none of this goes to suggest that Bosch was a gamer, 500 years before his time! It is the case, however, that the speculative concept of the megadungeon (Berti 2022), can shed some light not only on contemporary visions of The Garden of Earthly Delights, but also on the enduring appeal of the original into the post-digital age. Although Bosch’s storyline may be implacably linear, from sin through to punishment in hell, the visual effect of The Garden of Earthly Delights is that of an open world: the viewer’s eye and imagination are actively invited to wander.

3 Mapping Contemporary Delights: Fantasy, Sex and Space

3.1 Fantasy

Hieronymus Bosch must have lived in two different worlds: the real one around him, and the universe of his imagination.

(Ilsink, Koldeweij 2016, 9)

The visual universe presented in The Garden of Earthly Delights is compellingly weird. Structures built of rocks, plants and alchemical glassware dominate landscapes populated by hybrid creatures, lithe bodies and grotesque demons. Proportion is reimagined, enabling naked couples to ride giant birds or play inside oversized fruits, while everyday objects such as knives or musical instruments take on new roles in hell. It is little surprise, then, that one of the most commonly used adjectives to describe Bosch’s work is ‘surreal’. Surrealism itself has long been associated with Bosch, and his ingenious fantasies continue to attract contemporary surrealists across a range of media.

Links with The Garden of Earthly Delights can be found in a number of works by pioneering artists of the early twentieth century. Miro’s The Tilled Field (1923), features stylized plant forms, birds and a huge ear which echo imagery from Bosch’s triptych, while Dalí appears to have borrowed the head-shaped rocks from Paradise (albeit turned on their sides) for The Great Masturbator (1929). Frida Kahlo repurposes a giant bird from the central panel in her dreamscape, What the Water Gave Me (1938) and Max Ernst included the Dutch master in his word-collage Favorite Poets Painters of the Past (1942).

However, as Tessel Bauduin has shown (2016; 2017), it was critics, curators and dealers who first linked surrealist artists with Bosch, so providing impetus for artistic appropriation. Alfred H. Barr Jr., in his exhibition Fantastic Art, Dada and Surrealism (9 December 1936‑17 January 1937, MoMA, New York) argued for a super-genre of ‘fantastic art’ which crossed chronological boundaries to reflect:

the deep-seated and persistent interest which human beings have in the fantastic, the irrational, the spontaneous, the marvelous, the enigmatic, and the dreamlike. (Barr 1936, 9)

In Barr’s view, Bosch was a groundbreaker, who: “transformed traditional fantasy into a highly personal and original vision which links his art with that of the modern Surrealists” (9).

Artists themselves apparently warmed to this interpretation. While André Bretón omitted Bosch from his Surrealist Manifesto (1924), his image essay for the exhibition First Papers of Surrealism (14 October-7 November 1942, Whitelaw Reid Mansion, New York) opens with the fountain from Paradise.

Fast-forward to Lowbrow – also known as Pop Surrealism – and Bosch appears again as the go-to reference for curators and commentators alike.4 Mark Ryden is one of the movement’s best known figures and in the curator statement to the artist’s exhibition Wondertoonel (Frye Art Museum Seattle, November 2004-February 2005; Pasadena Museum of Californian Art, February 2005-May 2005), Debra Byrne describes Ryden’s work as carnivalesque, identifying this genre as: “a strain of visual culture rooted in such works as Hieronymus Bosch’s Garden of Earthly Delights” (Byrne 2005).

4 Lowbrow traces its origins to the pop culture, comic and underground cartoon aesthetics of 1960‑70s Los Angeles and has become more widely known since the early 1990s, particularly through the impact of publications such as Juxtapoz and Hi Fructose. For an overview of the genre, see Anderson 2004.

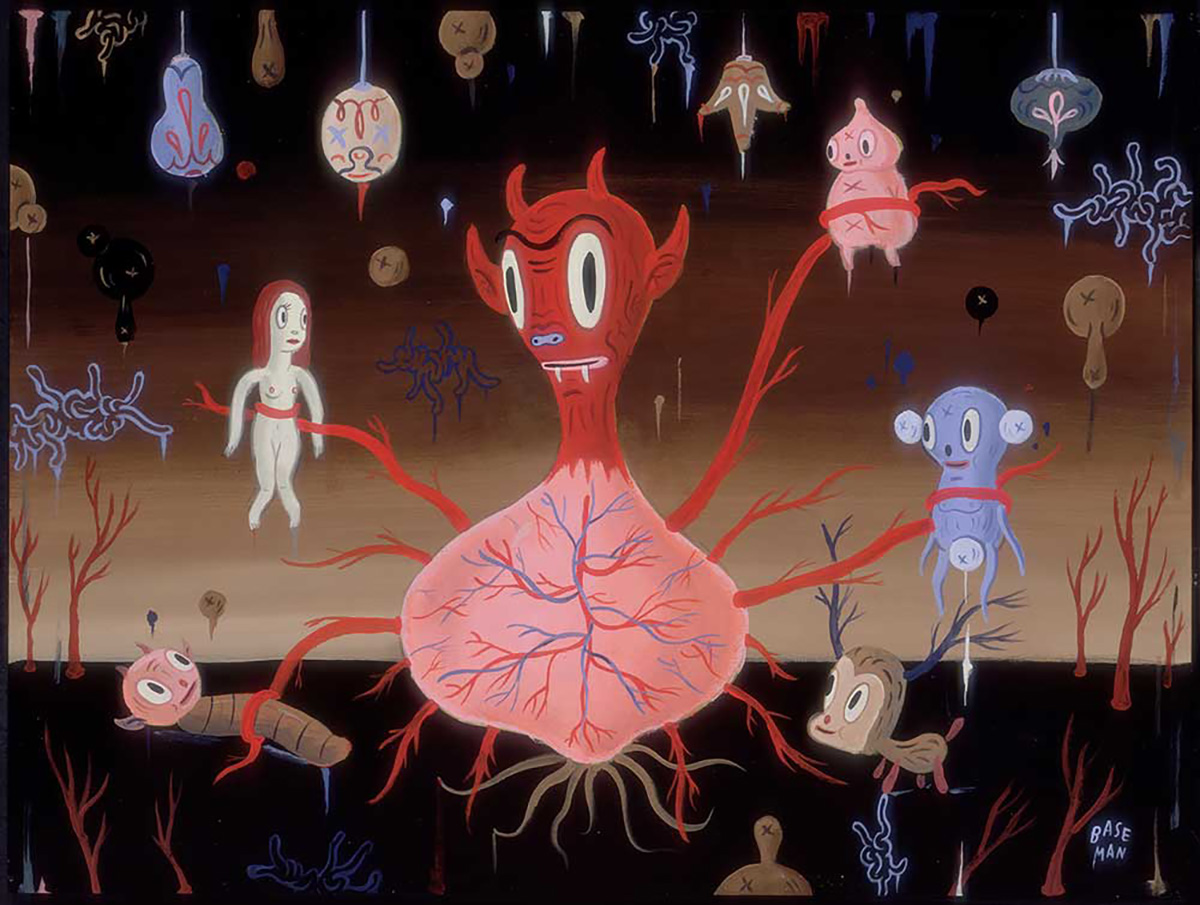

The exhibition Within The Garden of Earthly Delights hosted by Outré Gallery, Melbourne, in 2019 (6‑24 April) brought together Bosch-inspired pop surrealist and fantasy works by over 30 different artists including Peca, Travis Lampe and Roby Dwi Antono. Gary Baseman – another figure often associated with the Lowbrow scene – had already referenced Bosch’s triptych back in 2005 with a collection of paintings entitled The Garden of Unearthly Delights. In these works, the artist humorously tackles Freud’s pleasure principle, depicting demons as cheeky cartoon figures which force our suppressed desires into action [fig. 3]. More recently, digital surrealists such as GIF artist Sholim or the animated video creators, Cool 3D World, have also responded to Bosch in Heaven x Hell Series (2020) and El rey de la vida (2018) respectively.

Figure 3 Gary Baseman, Devil Heart. 2005. Acrylic on wood panel. 45.7 × 61 cm. Courtesy of the artist. © Gary Baseman

Most often, however, Bosch crops up in press coverage and descriptions of work by pop surrealists not because of direct visual or conceptual referencing but because he is popularly understood as a pioneer in envisaging the type of fantastical worlds these artists depict. A summary of this effect is provided by Davor Gromilovic, a Serbian artist whose offbeat pencil drawings have provoked comparisons with Bosch:

We could say that Bosch is the great-great-grandad of this kind of work. He opened a really important door for later generations, for artists who explore their inner world, their imagination and fantasy. (Rhodes 2021, 80)

3.2 Sex

Sex is everywhere in the central panel of The Garden of Earthly Delights. Erotic scenes unfold inside a giant mussel shell, a transparent sphere or on the back of an oversized duck. In the blue central fountain, a bearded man touches a woman’s genitals, while in the foreground, an upturned character masturbates.5 Numerous visual elements such as fruits, fish or birds make direct symbolic reference to sexual activity, as mentioned in Section 2, and some of Bosch’s scenes have been linked to erotic games played at court during the late-Medieval period (Falkenburg 2016, 146‑8). Lust is clearly punished in Hell: the toad – a symbol of impurity, connected to the Devil – makes various appearances, including on the standard of a fallen knight and the chest of a naked woman.

5 Eric De Bruyn provides a fascinating analysis of this scene, linking the character’s apparently prayerful gesture with sexual activity (2016, 81‑3).

In contemporary approaches, sex is addressed by a number of artists who upend Bosch’s moralistic focus with erotic, celebratory and critical works. An outstanding example is the series Garden of Earthly Delights (2002‑05) by Raqib Shaw. Born in Calcutta, then raised in Kashmir and the UK, Shaw creates opulent paintings using materials including industrial paints, car enamel, glitter and semi-precious stones. His visual universe draws on a wide range of sources, such as Persian miniatures, Japanese decorative arts, Kashmiri prints, jewellery and textiles. Works from his Bosch-inspired series depict orgiastic paradises populated by hybrid creatures: Garden of Earthly Delights X (2004), held by MoMA New York, is set in an extravagant coral reef, while Garden of Earthly Delights VIII (2005) shows a Minotaur ejaculating into a cloud of brightly coloured butterflies. Alpesh Kantilal Patel (2012, 2) has explored how Shaw’s explicit carnivalesque “queers broad notions of South Asian masculinity”, while the artist himself points to a scene in Garden of Earthly Delights III, where a giant shrimp has sex with a man on a bed of seaweed, as a commentary on sexual preference (Daftari 2006). In an interview regarding this work, Shaw explains:

in this painting what I really wanted to deal with was the moment when we actually have an orgasm […] the work is made from a place of no inhibitions. There are no moral policeman [sic], there is no morality. It is what it is, and it is happy to be what it is.

A similar view is taken by the Canadian artist, Dave Cooper, whose oil painting Bosco Cooper (2018), depicts a cast of cartoonish oddballs enjoying a bizarre orgy. Nature itself seems to participate, with the landscape dominated by bulbous forms, penis-shaped plants and nipple-like flowers. Characters from Bosch’s original are humorously replaced: Adam is portrayed as a lascivious dog, Eve is a beaked bird with wide eyes and large breasts, while God, as described by the artist, is “just two giant cocks with eyes on the end” (Rhodes 2021, 26). In response to The Garden of Earthly Delights, Cooper presents a carnival of kinky sensuality and transgression. Like Shaw, he reworks Bosch’s moral tale as a celebration of sexual freedom, stating that:

As long as all those weirdos in my painting are consenting adults, then it’s all ok. In my mind, it’s not about good and bad any more. It’s just light, dark, cheerful, aggressive. (28)

A less permissive view was taken of Silvano Agosti’s, Il giardino delle delizie (1967) by Italian film censors, who initially cut more than 25 minutes from what is now regarded as:

a gem of modernist cinema […] a quintessential film of its age that can be viewed as a veritable time capsule, preserving the sizzling rebellious spirit of the Beat generation. (Petho 2014, 475)

Agosti’s debut feature borrows from Bosch in a work loaded with subtlety erotic imagery, which calls out the hypocrisy of bourgeois values and the Catholic church. The protagonists, Carla and Carlo, have married only because the former is pregnant; their honeymoon descends into physical and mental agony, translated on screen into a series of hallucinatory images. In the opening sequence, the bride gazes straight at the audience as she sensually takes a bite of a cherry – a clear reference to The Garden of Earthly Delights – before the camera lingers on equally suggestive scenes of a knife cutting into the wedding cake or the champagne glasses being filled. The circuit of bareback riders from Bosch’s central panel is quoted in a bizarre dance sequence in which fun-loving youths and a procession of altar boys appear in the same riverside setting. Less explicit than the cited works by Raqib Shaw or Dave Cooper, Silvano Agosti’s film translates Bosch’s innuendo-filled world into a series of elegant, lingering scenes and a searing indictment of marriage.

3.3 Space

In El jardín deshabitado (2008), Jose Manuel Ballester meticulously edited a digital reproduction of The Garden of Earthly Delights, erasing every character, animal and bird. The result is an eerie landscape, punctuated by the fantastical structures and organic forms of the original, which not only speaks of absence or memory but also serves as an invitation. In the viewer’s imagination, the question arises whether to repopulate or leave untouched this vacated world.

The notion of re-inhabiting Bosch’s triptych is common to various contemporary visions of the work. Lluis Barba’s Travellers in Time: The Garden of Delights (2007‑15) sees colour images of celebrities, tourists and brand logos invade a black and white reproduction of Bosch’s painting, while Carla Gannis harnesses the popular imagery of mobile messaging for The Garden of Emoji Delights (2014). Dan Hernandez reimagines the space itself: in the mixed media panel, GOED (2020), Bosch’s triptych is reworked as an open world game based on the map for The Legend of Zelda (Nintendo 1986). Populated by characters from video games, cartoons and late-Medieval paintings, this is literally a megadungeon. As the artist explains: “It’s an adventure story, a world that you would try to explore. […] In my mind, I think you could play it” (Rhodes 2021, 60, 64).

Cassie McQuater also recasts The Garden of Earthly Delights as a retro video game. In line with Hans Belting’s view of Bosch’s central panel as “a utopian vision of a world that never existed” ([2002] 2018, 54), in Angela’s Flood (2020), McQuater custom-builds a pleasure garden for three female characters. Angela Belti, Super Kurara (both Power Instinct, Atlus for Arcade, 1993) and Deliza (Dragon Master, UNiCO Electronics for Arcade, 1994) blow kisses, rollerblade and show off their muscles in a bespoke environment which subverts the violent, male-dominated narratives for which they were first developed [fig. 4].

Physical, not only digital, re-inhabitation of Bosch’s masterpiece is central to other contemporary iterations. In Lech Majewski’s film The Garden of Earthly Delights (2004), the protagonists re-enact erotic scenes from the painting, which are recorded, played and re-recorded to create a visual narrative of multiple layers. Audiences themselves shape Jeffrey Shaw’s, Going into the Heart of the Center of the Garden of Delights (1986), a site-specific piece created for Vleeshal, the Netherlands, in which visitors’ movements along a 30-metre pathway generate sequences of digitally processed images drawn from works by Bosch, Yves Klein and Nagisa Oshima. Martha Clarke, meanwhile, translated Bosch’s painting into dance in 1984 (re-staged in 2008), employing harnesses and flying techniques in a visceral adaptation, which is still revered. Theatre critic Charles Isherwood summarizes:

This singular work of dance theater is without doubt one of the most eerily hypnotic spectacles of flesh in motion ever put on a New York stage. (The New York Times, 19 November 2008)

These examples link with a view of Bosch’s work as an active experience, as outlined in Section 2. The Garden of Earthly Delights, however, has served not only as a world to inhabit or repopulate, but as an enabling space, a site for experimentation. In this respect, The Garden of Earthly Delights (1981) by Stan Brakhage is the most remarkable example.

Figure 4 Cassie McQuater. Angela’s Flood (detail). 2020. Single-channel colour video of HTML work. 12′57″. Colección SOLO, Madrid. Courtesy of the artist and Colección SOLO. ©Cassie McQuater

To make the two-minute film, Brakhage pressed leaves, grasses and flowers between strips of celluloid, creating 2469 frames which, in movement, translate into a unique synaesthetic experience for the viewer. The work is often seen as a partner to Mothlight (1963), the artist’s highly influential collage film made using moth wings and petals. In an interview with Scott MacDonald, the avant-garde filmmaker explained his feelings about Bosch’s original:

At the time I made The Garden, I was very annoyed with Hieronymus Bosch’s painting of the same name, which envisions nature as puffy and sweet, while the humans are suffering all these torments. After all, nature suffers as well. As a plant winds itself around a rock, in its desperate search for sunlight, it undergoes its own torments. We are not the only ones in the world. (MacDonald 2005, 94)

In a present-day shaped by climate crisis, Brakhage’s words seem prescient. In centring our gaze on nature, his work aligns with other environment-focussed approaches to Bosch, such as those brought together in the exhibition Garden der irdischen Freuden (Gropius Bau Berlin, 26 July-1 December 2019) and accompanying catalogue (Rosenthal 2019). Within the scope of this article, however, the most significant feature of Brakhage’s film is the artist’s ability to free the eye from perspective, logic or preconception; to take the viewer on what he describes as “adventure of perception” (Brakhage quoted in Petho 2014, 482).

A related adventure is provided by Enrique del Castillo, whose Umbráfono II (2021) is a machine which reads patterns on 35mm film and turns them into sound. For the exhibition The Garden of Earthly Delights through the Artworks of Colección SOLO, discussed in Section 5, del Castillo developed five compositions inspired by Bosch’s triptych and the polyphonic music of its time. Another “experiment about perception” (Rhodes 2021, 158), as the artist describes the piece, is The Garden of Ephemeral Details (2020) by Mario Klingemann. In real time, a suite of algorithms developed by Klingemann engages with a digital image of Bosch’s original, transforming its visual content through a continuous cycle of analysis, change and restoration. Artificial intelligence brings its unique ‘eye’ to Bosch, reworking the triptych into a fluid screenscape of abstract forms.

4 Digital Specula

4.1 Microcosm

I don’t know if Bosch is saying, “This is bad, this is good”. He gives me many, many possibilities and, for me, this complication is very interesting. So when I make my video works, what I want to do is the same: I want to make very open artworks.

(R. Rhodes, Interview with Miao Xioachun, 24 April 2021)

As outlined in Section 2, The Garden of Earthly Delights resonates with present-day aesthetics explored in Kwastek (2015), Jagoda (2016) and Robson, Tavinor (2018), among others, as particularly appreciative of interactive, non-linear media. The layered, multiple-narrative, inhabitable character of Bosch’s original also fits with the concept of a megadungeon as “interconnected, layered, maze-like, procedural” (Berti 2022). It is perhaps for this reason that artists have found in the work a timely and attractive candidate for re-writing in digital media.

Reindert Falkenburg has argued (2011; 2016) that The Garden of Earthly Delights can be understood as a ‘princely mirror’, the visual equivalent of writings such as The Education of a Christian Prince (1516) by Erasmus or Castigliano’s Il Cortegiano (1528). This section highlights three works by contemporary digital artists which bring Bosch’s speculum into the present-day. In each case, the viewer is presented not with simple mirrors to reality but with open worlds to experience, inhabit and discuss.

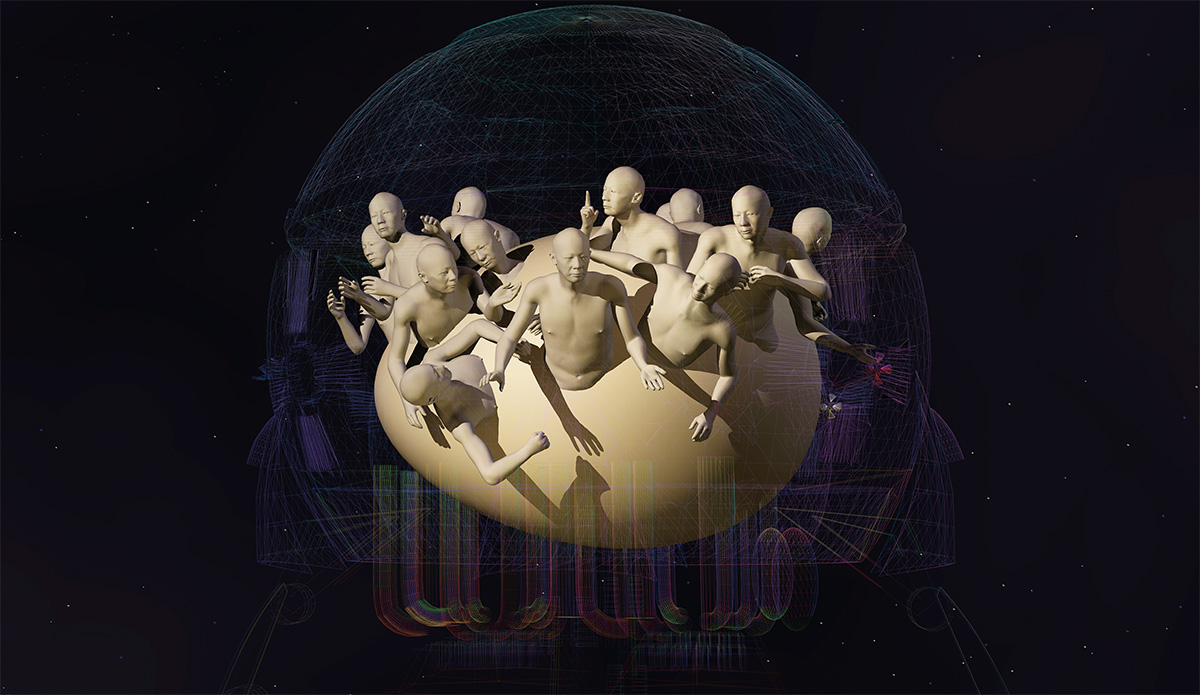

The first of these digital reworkings, Microcosm (2008), actually comprises two pieces: a nine-panel C-print installation and a 16-minute video, generally exhibited together [fig. 5]. Directly inspired by Bosch’s The Garden of Earthly Delights, this digital project was developed over an 18-month period by the Chinese artist, Miao Xiaochun.

Figure 5 Miao Xiaochun, Microcosm. 2005. Single channel video animation. 15′55″. Courtesy of the artist. ©Miao Xiaochun

It forms part of his Renaissance Trilogy, together with The Last Judgement in Cyberspace (2005), based on Michelangelo’s fresco in the Sistine Chapel, and H20 (2007), after Cranach’s The Fountain of Youth (1546).

To create Microcosm, Xiaochun developed a digital 3D model in which all the figures in the original work are replaced, many with references to contemporary life. Adam becomes a robot, tirelessly coding a new future, and Eve is replaced by the Venus de Milo, unable to reach out for the forbidden fruit as she has no arms. The central fountain is a glistening mass of liquefied vehicles, while the riders carry plastic bottles, tins or kitchen utensils. Weapons, computers and mobile devices abound, plastic animals outnumber their wild counterparts and every character is exactly the same: a digital rendering of the artist’s naked body. As Miao Xioachun explains:

A body is more of a symbol. Once a body puts on clothes, there will be some sort of representation, for example, a certain time, a certain social class. If I only use the body, these representations do not exist. […] Then we can talk about abstract issues, like birth and death. (Du 2009)

In this respect, Bosch’s approach is similar. Hans Belting describes Bosch’s characters as “ageless”,“doll-like” and “devoid of individual traits” ([2002] 2018, 54), while Nils Büttner sees them as “flat figures that are almost pictograms” (2014, 283).

By using his own body in Microcosm, Miao Xiaochun literally inhabits the work. His creative process itself also involved journeying inside his version of Bosch’s triptych:

I build the virtual world and then I can walk inside. I can take photographs with a virtual camera and make video with a virtual video camera. All of this is virtual; it only exists in the software. (R. Rhodes, Interview with Miao Xioachun, 24 April 2021)

It is not only the artist who steps inside Microcosm. Each panel of the nine-part work offers three different scenes and the panels themselves are presented as a continuum of three triptychs, with the side wings at 45º angles from the wall. The effect is that when a viewer stands at any point in the installation, they are able to appreciate numerous other perspectives. The artist summarizes his aim as follows:

To see death from birth, and birth from death;

To see hell from heaven, and heaven from hell;

To see the end from the beginning, and the beginning from the end.

(Xiaochun 2008)

These multiple perspectives are further complemented by the video, whose sweeping shots lift the viewer above, below and into the action. Xiaochun describes it as “a river, flowing from beginning to end” (R. Rhodes, Interview with Miao Xioachun, 24 April 2021) and the viewer is hurled inside. As Huang Du explains (2009) the title itself refers to perspective and our limitations in understanding, playing on the Chinese idiom “looking up to the sky from the well” and the literary translation for “microcosm” as “looking down the well from the sky”.

Xiaochun builds a new world and brings the viewer inside it to meditate on the nature of progress, our relationship with technology and how we relate to our environment. In offering numerous perspectives on the same scene, Microcosm links with traditional Chinese paintings, in which the same character can appear at various different points.6

6 Further information on how Miao Xiaochun blends references to Chinese philosophy and Western art are provided in Ippolito 2017 and Zielinski 2010.

For the artist, this approach strengthens the work’s emotional impact: “It puts more emphasis on subjective feelings. […] When I see the scenes, I feel like I see the whole story” (Du 2009).

With Microcosm, then, Miao Xiaochun offers the viewer an open world not only to inhabit and explore, but to ‘feel’. A mirror to the present, in which the viewer is an active participant.

4.2 The Garden of Error and Decay

In The Garden of Error and Decay (2010) by Michael Bielicky and Kamila B. Richter, the spectator plays an even greater role. In this interactive work, an animated pictogram appears on the screen every time a disaster-related topic is discussed on Twitter. Using a joystick located in the exhibition space, viewers can shoot at these symbols, choosing to multiply each disaster or eliminate it from the ever-changing screenscape [fig. 6].

Figure 6 Installation view of The Garden of Error and Decay (2010) by Michael Bielicky and Kamila B. Richter. Courtesy of the artists. ©Michael Bielicky and Kamila B. Richter

The pictographs themselves border on cute. There are simple stick-characters with large round eyes, comic-like skeletons and humorous references to historical figures, as well as geometric trees and animals reminiscent of those found in children’s books. Bosch’s The Garden of Earthly Delights is referenced with giant cherries and strawberries. The inoffensive appearance of these pictograms contrasts with the hard data driving their presence on screen: behind each cartoonish figure lies an environmental disaster, terror attack, war, financial crisis or health emergency and the Twitter conversation surrounding it. This disjunction inevitably raises questions about the ways in which horror is depicted, discussed or even commodified.

It is worth noting that real events also feature in Bosch’s original, although most analyzes have centred on symbolism or abstract notions of sinful behaviour. One group of riders bears a porcupine standard, the personal device of King Louis XII of France, an image which would surely have resonated with viewers at a time of intense rivalry between the kings of France and the dukes of Burgundy (Falkenburg 2016, 154). Depictions of exotic animals such as the elephant or giraffe draw on fifteenth century travel journals, for example by Cyriacus of Ancona, and the dating of Bosch’s painting is hugely relevant in itself. The Garden of Earthly Delights is thought to have been completed in the late 1490s, with the European worldview upended as a result of Columbus’s voyages. Hans Belting sees a direct link between these real-world events and Bosch’s imaginative central scene:

The conquest and charting of the world irrevocably pushed the existence of a terrestrial Paradise into the realm of dreams. (Belting [2002] 2018, 99)

Contemporary events underpin The Garden of Error and Decay, described by the artists as “a real-time, data-driven narrative” (Bielicky, Richter 2011). Spectators are called not only to observe or reflect on the present, but to shape a new world on screen. However, when a viewer shoots to eliminate disaster pictograms, other data comes into play. Real-time stock market information is also fed into the piece, and it is this data – not the spectator’s actions – which ultimately dictates whether disasters proliferate or recede.

The Garden of Error and Decay, then, is an interactive allegory, addressing the relationship between the individual and global events. It reflects the abundance of data in our networked present, gamification, and the endless opportunities for online debate: speculatio transposed to and transformed by social media. At the same time, Bielicky and Richter highlight the impotence of the individual, unable to impact on world-changing events even if they choose to act.

4.3 Speculum

In line with the basic structure of Bosch’s original, Speculum (2016‑19) is a three-channel video installation developed using 3D digital animation [fig. 7]. In each scene, borrowings from The Garden of Earthly Delights are adeptly reworked and combined with references to popular culture, including celebrities, cartoon characters and memes. Mass behaviour, digital identity and ubiquitous technologies are all addressed in a moving triptych which employs brand-new symbolism to present a crude yet entertaining mirror of contemporary life.

Figure 7 Installation view of Speculum (2016‑19) in the exhibition The Garden of Earthly Delights through the Artworks of Colección SOLO. Madrid, Matadero (7 October 2021-27 February 2022). Photograph: Alberto Triano. Courtesy of Colección SOLO. ©SMACK

The digital arts collective, SMACK (Ton Meijdam, Thom Snels and Béla Zsigmond), developed Paradise, the central panel of Speculum, as a commission for the exhibition Nieuwe lusten, held at the MOTI in Breda from 2 April to 31 December 2016.7 Described in a Jheronimus Bosch Art Center review as “the most successful part of the exhibition” (18 July 2016, https://jeroenboschplaza.com/recensie/nieuwe-lusten-2016/?lang=en), Paradise was widely covered online and later attracted the attention of Ana Gervás and David Cantolla, the founders of Colección SOLO Madrid. They acquired the work and subsequently commissioned SMACK to create Eden and Hell, so completing the digital triptych.

7 This exhibition formed part of the Bosch500 programme to commemorate 500 years since the artist’s death. MOTI (Museum of the Image) Breda is now the Stedelijk Museum Breda.

Mass behaviour is a central theme in SMACK’s artistic practice and Speculum contains numerous references to group dynamics and identity. All three scenes, for example, feature plants, structures or bulbous creatures formed of many different bodies or heads, some of which are recognisable celebrities. Visually, these clusters of heads recall the giant forest fruits in The Garden of Earthly Delights, yet as SMACK explain, their imagery speaks directly to the present: “The idea was to show how a community works, online or in the analogue world. It’s the crowd compressed into one creature” (Rhodes 2021, 116).

In a contemporary environment shaped by social media echo chambers and bot-enhanced misinformation, the relevance of this imagery is clear. Speculum’s population, however, does not operate exclusively in groups: each character in Paradise is trapped in an individual loop, a reflection of self-obsession, isolation or loneliness.

Pervasive technology is also explored through skilful borrowings and revamped symbolism. In the left panel of The Garden of Earthly Delights, an owl – often understood as a symbol for evil – gazes out from the central structure, a scene echoed in Bosch’s The Trees Have Ears and The Field Has Eyes (c. 1500), which references a Middle Dutch proverb on the idea that we are always observed (Ilsink, Koldeweij 2016, 80). In Speculum, SMACK update these same concerns for the Information Age: even in the pastel calm of Eden, plants sprout eyes, drones swarm overhead and tech-animal hybrids roam. In this artificial idyll – where God has been replaced by Newton, and real animals forced out by giant, pixelated cats – the tools of permanent surveillance are all in place. Camera-creatures also feature in Paradise, while in Hell a businessman is harried by CCTV apparatus.

The climate crisis is touched upon through nature commoditized and transformed: in Paradise, packaging grows on trees, chickens are pre-fried and a pig is but a walking mass of sausages. Ethical dilemmas around artificial intelligence are reflected in Hell, where robots are punished alongside humans. The plight of refugees is spotlighted too: a city burns in the distance, as in Bosch’s original, but in SMACK’s version, those trying to escape are even refused entry to Hell. Like The Garden of Earthly Delights, Speculum is a labyrinth of visual tales, which invites the eye to explore.

In Section 2, Bosch’s triptych was described not only as a visual journey but as a physical experience, an environment to step inside. The ‘immersive’ or ‘entertainment’ appeal of the original is underscored by the huge number of copies created in the sixteenth century, particularly in the large-format medium of tapestry (Büttner 2014, 296). The Duke of Alba, commissioning a textile version of The Garden of Earthly Delights, even ordered “Fait fere les personnaiges plus grant / the figures to be made still larger” (Belting 2018, 83). Speculum – like Microcosm and The Garden of Error and Decay, already discussed – is heir to this ‘physicality’ of Bosch. These digital mirrors of society are conceived not simply to look at, but to set foot inside and debate.

5 The Garden of Earthly Delights through the Artworks of Colección SOLO

An understanding of Bosch’s iconic triptych as an open world, as both a visual and physical adventure, was central to the development of the exhibition The Garden of Earthly Delights through the Artworks of Colección SOLO, held at Matadero Madrid from 7 October 2021 to 27 February 2022. Of course, this exhibition was not the first to draw inspiration from The Garden of Earthly Delights, which has attracted curators on numerous occasions. Noteworthy examples include the eponymous exhibition of photographs by Edward Weston and Robert Mapplethorpe, shown at the California Museum of Photography, Baltimore Museum of Art and the International Center for Photography, New York, in 1995, or the Lowbrow show at Outré Gallery Melbourne, mentioned in Section 3. In 2016, the anniversary of 500 years since Bosch’s death saw a wealth of contemporary art events, including Nieuwe lusten at MOTI Breda and more recently, Gropius Bau Berlin hosted Garden der irdischen Freuden (2019), centred on the garden itself as a space for critical reflection. In the context of this paper, however, The Garden of Earthly Delights through the Artworks of Colección SOLO is particularly relevant: the exhibition discourse, design and publication were all informed by a vision of Bosch’s triptych as interactive art.

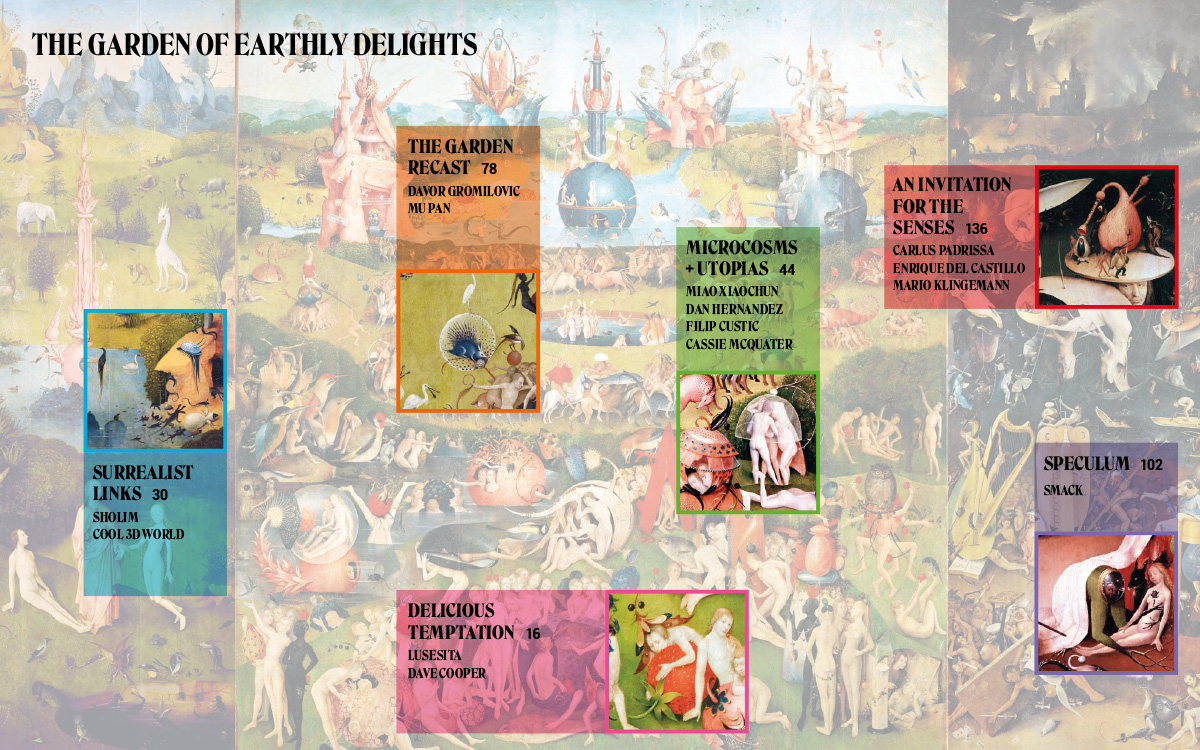

Since 2016, Colección SOLO has acquired and commissioned contemporary artworks inspired by The Garden of Earthly Delights. In 2021, these were brought together for the first time in an exhibition coproduced with and hosted by Matadero Madrid, a public arts centre and former slaughterhouse in the Spanish capital. Works by fifteen artists were featured, across media including painting, sculpture, sound art and digital animation. These were presented in six thematic capsules based on different appreciations of Bosch’s original: An Invitation for the Senses, Delicious Temptation, Surrealist Links, Microcosms and Utopias, The Garden Recast and Speculum.

As discussed in Section 2, The Garden of Earthly Delights takes the viewer on a chromatic journey from a grisaille exterior, through the triptych’s doors and into total colour. This experience was translated into the exhibition design through background greys set against neon colour gradients [fig. 8].

Figure 8 Exhibition poster for The Garden of Earthly Delights through the Artworks of Colección SOLO. Madrid, Matadero (7 October 2021-27 February 2022). Designer: Ruben Montero. Courtesy of Colección SOLO. ©ColeccionSOLO

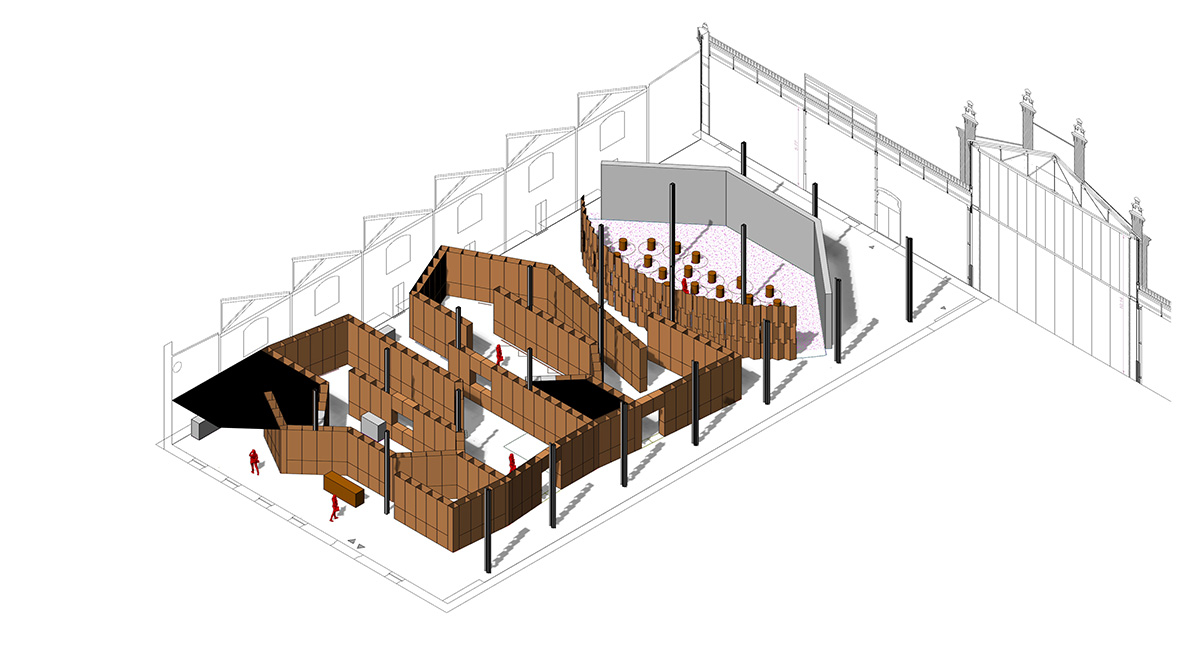

These, in turn, drew on the saturated tones of featured digital artworks such as Speculum by SMACK or Cassie McQuater’s Angela’s Flood. The spatial concept for the exhibition, developed by estudioHerreros, underlined the same notion of crossing from one reality into another. For the 1,000 m² Nave 16 at Matadero Madrid, the architects developed a labyrinth-like structure, in which visitors gradually encountered each artwork and thematic area [figs 9‑10].

Figure 9 Axiomatic projection of the spatial design for The Garden of Earthly Delights through the Artworks of Colección SOLO. Madrid, Matadero (7 October 2021‑27 February 2022). estudioHerreros. Courtesy of estudioHerreros. ©estudioHerreros

Figure 10 Installation view of The Garden of Earthly Delights through the Artworks of Colección SOLO. Madrid, Matadero (7 October 2021‑27 February 2022). Photograph: Luis Asín. Courtesy of estudioHerreros and Luis Asín. ©Luis Asín

The space itself was accessed through a simple doorway hung with a chain curtain. After traversing a welcome area with an information desk and access to lockers, visitors continued through a covered ‘sound tunnel’ containing Enrique del Castillo’s Umbráfono II.

Rather than a large, open-plan area in which various artworks compete for attention, estudioHerreros developed spatial sequences which enabled exploration at a calmer pace.8 Choice was also central.

8 EstudioHerreros designed the Munch Museum in Oslo, the National Museum of China, Shenzhen, and the Wetland Museum in Fetsund, Norway, among others. Juan Herreros’s preference for sequences of explorable, interlinked spaces is particularly clear in his design for the exhibition halls at the Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía (MNCARS) and Espacio SOLO, both in Madrid. More information on the latter is provided in Panetsos, Manis, Soulis 2021, 101‑40.

For example, visitors could decide whether or not to step onto the vibrating floor of La Fura dels Baus /Carlus Padrissa’s installation, El jardín de las delicias (2021), or to take a seat inside the dedicated viewing area for Miao Xiaochun’s Microcosm, while two openings in the maze allowed exhibition goers to re-enter or take alternative routes. The structure itself was built of cardboard, a modest, easily recyclable material whose earthy tone contrasted with the bright digital works exhibited. Finally, the height of this cardboard labyrinth was meticulously calculated so that visitors could not glimpse Speculum – displayed on LED screens measuring a total length of 21 metres and a height of 4 metres – until they turned the final corner.

A significant outcome of this expositive megadungeon was to lengthen visitor experience. Over 92,000 people saw The Garden of Earthly Delights through the Artworks of Colección SOLO, with viewers spending longer than average inside the exhibition space.9 The dedicated ‘forum’ for Speculum – with flooring and cardboard seats – enabled visitors to appreciate its wealth of narrative scenes and discuss the work in situ, while the scale and element of surprise built into the exhibition of this work achieved the same ‘wow effect’ of Bosch’s triptych described by Antonio Beatis back in 1517.10

9 Visitor numbers provided by Matadero Madrid, together with anecdotical evidence gathered in conversation with exhibition staff.

10 MOTI Breda reports a similar experience of showing Paradise in 2016, with visitors spending longer than average inside the viewing space (conversations with the curator, Mieke Gerritzen). For Triennial 2023 at NGV Melbourne (3 December 2023‑7 April 2024), Speculum will also be exhibited large-format (approximately 14 metres in length), in a dedicated area, together with the artists’ 10 Characters Series (2019‑20).

An explorative, non-linear approach was also taken with regard to the exhibition catalogue (Rhodes 2021). Although the publication contains the same six thematic areas as the exhibition, the reader is invited to explore them in the order they prefer. Instead of a traditional contents page, Bosch’s original is used by way of a map, with certain scenes highlighted as routes into the book’s different sections [fig. 11]. Similarly, the habitual ‘essays followed by image catalogue’ format is rejected in favour of a layout in which text and artwork images function in dialogue. In the chapter introductions, key concepts even appear in larger font sizes, providing an accessible overview for readers who prefer to skim the text. Finally, the cover design and chapter openers reflect a digital aesthetic, with individual squares – or pixels – hinting at the multiple layers of information to be explored inside.

Figure 11 Contents page for The Garden of Earthly Delights exhibition catalogue. Designer: Susana Pozo. Courtesy of Colección SOLO. ©Colección SOLO

6 Conclusions

The Garden of Earthly Delights is a treasury of visual tales, an adventure for the eye and the imagination which seems to offer something new every time we revisit the work. To the contemporary gaze, shaped by digital experience, the countless narrative vignettes, scenes within scenes and interconnected spaces comprise universes to zoom in on and discover. Together with the imaginative genius of Bosch’s imagery, it is perhaps this open, multi-layered structure which explains the enduring appeal of the work for post-digital generations.

Three broad areas of interaction with The Garden of Earthly Delights – fantasy, sex and space – have been mapped to illustrate some of the different routes chosen by contemporary artists, with parallels between the original painting and its present-day counterparts highlighted. Although the selection featured in this article is not intended as an exhaustive list, it certainly attests to the variety and artistic quality of expression ‘after Bosch’. The artworks presented here are not mere copies or appropriations, but highlights of contemporary creativity in their own right. From surrealist beginnings through to iconic works of avant-garde film, new media or Raqib Shaw’s identity-affirming series of paintings, contemporary references to Bosch are characterized by a willingness to experiment and explore.

Special consideration has been given to the digital works Microcosm, The Garden of Error and Decay and Speculum: like Bosch’s triptych, all three are alternative worlds conceived as physical experiences and starting points for critical debate. It is argued that Bosch’s masterpiece lends itself to digital reworking because of its layered, explorable nature; the original’s wealth of intersecting narratives transposes naturally into moving imagery crafted using 3D animation techniques. The cited works re-shape Bosch’s open world, infusing it with movement and replacing late-Medieval symbolism with references to contemporary existence. A brief case study of The Garden of Earthly Delights through the Artworks of Colección SOLO has also been provided to illustrate how this experiential reading of Bosch was translated into a major exhibition.

To conclude, the story of contemporary adventures with The Garden of Earthly Delights is a tale of interconnections over time. From late-medieval double entendre to a new symbolism of memes, pictograms and celebrities; from an obsession with lust to celebrations of diversity; from oils through to celluloid, 3D animation and glitch; from a Renaissance ‘mirror for princes’ to sharp reflections of the twenty-first century. In short, from one open world to myriad others.

Bibliography

Anderson, K. (ed.) (2004). Pop Surrealism: The Rise of Underground Art. San Francisco: Ignition Publishing/Last Gasp.

Bauduin, T. (2016). “Bosch als ‘surrealist’: 1924‑1936”. Ex Tempore, 35, 84‑98.

Bauduin, T. (2017). “Fantastic Art, Barr, surrealism”. Journal of Art Historiography, 17, December, 1‑23. https://arthistoriography.wordpress.com/17-dec17/.

Belting, H. [2002] (2018). Hieronymus Bosch, Garden of Earthly Delights. Munich; New York: Prestel Verlag.

Berti, P. (2022). “Megadungeons and Roguelike Reality”. Megadungeon: New Digital Volumetries in Art and Media = International Conference Proocedings (Venice, Ca’ Foscari University of Venice, 4 October 2022).

Bielicky, M.; Richter, K. (2011). “The Garden of Error and Decay”. Leonardo, 44(4), 356‑7.

Büttner, N. (2014). “No Flesh in the Garden of Earthly Delights”. Ensslin, F.; Klink, C. (eds), Aesthetics of the Flesh. Berlin: Sternberg Press, 273‑99.

Byrne, D. (2005). “In the Pink of the Carnivalesque”. Wondertoonel = Exhibition Curator Statement (Frye Art Museum, Seattle, November 2004-February 2005; Pasadena Museum of California Art, February 2005-May 2005). https://www.markryden.com/curator-statement-wondertoonel.

Daftari, F. (2006). Interview with Raqib Shaw for the exhibition “Without Boundary: Seventeen Ways of Looking” (MoMA New York, 26 February-22 May 2006). https://www.moma.org/audio/playlist/196/2624.

De Bruyn, E. (2016). “Texts and Images: The Sources for Bosch’s Art”. Maroto 2016a, 73‑89.

Dixon, L. (2003). Bosch. London; New York: Phaidon

Du, H. (2009). Miao Xiaochun: Microcosm – A Modern Allegory. Interview with Miao Xiaochun, Beijing, 8 February 2009. Transl. by Hao Yanjing. https://www.miaoxiaochun.com/Texts.asp?language=en&id=19.

Falkenburg, R. (2011). The Land of Unlikeness: Hieronymus Bosch, “The Garden of Earthly Delights”. Zwolle: W Books.

Falkenburg, R. (2016). “In Conversation with The Garden of Earthly Delights”. Maroto 2016a, 135‑55.

Fraenger, W. (1947). Hieronymus Bosch. Das Tausendjhärige Reich. Grundzüge einer Auslegung. Coburg: Winkler-Verlag.

Gibson, W. (2003). “The Strawberries of Hieronymus Bosch”. Cleveland Studies in the History of Art, 8, 24‑33.

Gombrich, E.H. (1967). “The Earliest Description of Bosch’s Garden of Delight”. Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes, 30, 403‑6.

Gossart, M. (1907). La peinture de diableries á la fin du Moyen Age: Jérome Bosch, le “faizeur de Dyables” de Bois-le-Duc. Lille: Imprimerie centrale du Nord.

Harris, L. (1995). The Secret Heresy of Hieronymus Bosch. Edinburgh: Floris Books.

Ilsink, M.; Koldeweij, J. (2016). Hieronymus Bosch, Visions of Genius = Exhibition Catalogue (Hertogenbosch, 13 February-8 May 2016). s-Hertogenbosch: Het Noordbrabants Museum

Ippolito, J. (2017). “Electronic Media Art from China: New Visions Bring Messages from the Distant Past”. Leonardo, 50(2), 160‑9.

Jagoda, P. (2016). Network Aesthetics. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Koldeweij, J. (2001). “The Oeuvre of Hieronymus Bosch”. Van Oudheusden, J.; Vos, A. (eds), The World of Bosch. ’s-Hertogenbosch: Adr Heinen, 96‑133.

Kwastek, K. (2015). Aesthetics of Interaction in Digital Art. Cambridge (MA): MIT Press.

MacDonald, S. (2005). A Critical Cinema 4: Interviews with Independent Filmmakers. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Marijnissen, R. [1987] (2007). Hieronymus Bosch: The Complete Works. Antwerp: Mercatorfonds.

Maroto, P. (ed.) (2016b). Bosch. The 5th Centenary Exhibition = Exhibition Catalogue (31 May-11 September 2016). Madrid: Museo Nacional del Prado.

Maroto, P. (2016b). “Bosch and His Work”. Maroto 2016a, 17‑71.

Mittman, A. (2002). “Inverting the Panopticon: Google Earth, Wonder and Earthly Delights”. Literature Compass, 9(12), 938-54. https://doi.org/10.1111/lic3.12019.

Panetsos, G.; Manis, N.; Soulis, N. (eds) (2021). “Espacio SOLO: Estudio Herreros”. DOMa, 6, 101‑40.

Patel, A. (2012). “Open Secrets in ‘Post-Identity’ Era Art Criticism/History: Raqib Shaw’s Queer Garden of Earthly Delights”. Darkmatter, 9(2). https://www.alpeshkpatel.com/book-chapters-journal-articles.

Petho, A. (2014). “The Garden of Intermedial Delights: Cinematic ‘Adaptations’ of Bosch, from Modernism to the Postmedia Age”. Screen, 55(4), 471‑89.

Ramirez, J. (2017). “Garden of Earthly Delights by Hieronymus Bosch – with Waldemar Januszczak”. Art Detective, January 2017. Podcast. https://open.spotify.com/episode/0J4Grk52JRhidxIbIiq3vg.

Rhodes, R. (2021). The Garden of Earthly Delights = Exhibition Catalogue (Madrid, 7 October 2021‑27 February 2022). Madrid: Colección SOLO.

Robson, J; Tavinor, G. (eds) (2018). The Aesthetics of Videogames. New York: Routledge.

Rosenthal, S. (2019). Garten der Irdischen Freuden = Exhibition Catalogue (Berlin, 26 July-1 December 2019). Berlin: Silvana Editoriale.

Xiaochun, M. (2008). Microcosm = Artist Statement. Transl. by Hao Yanjing. https://www.miaoxiaochun.com/Texts.asp?language=en&id=21.

Zielinski, S. (2010). “Discovering the New in the Old: The Early Modern Period as a Possible Window to the Future?”. Grosenick, U.; Ochs, A. (eds), Miao Xiaochun 1999‑2009. Cologne: DuMont Buchverlag.